A Tale of Two Earthquakes and the Systemic Failure of a Nation

Reflections on the 1999 İzmit and 2023 Turkey-Syria earthquakes, and the interrelationship between democracy, corruption, and natural disasters in Turkey.

I was four years old on August 17, 1999, when the İzmit earthquake with a magnitude of 7.6 struck in İstanbul. That night led to 18,000 deaths, physically disabled many more, and traumatized even greater numbers in under two minutes. The sky was a dark red color at dawn, and it became crisp blue as the sun came up. I remember the huge crack on our living room wall, living in the car due to the fear aftershocks, and my grandfather with a dress hanger strapped to his broken back to hold him still.

In the earthquake’s aftermath, almost every paper used a version of the same headline and described society as having been left sahipsiz, which translates as unowned, unattended, derelict, without a guardian, or uncared for. The 1999 earthquake had hit in a time of economic crisis and political instability, and the ineffectiveness of the public response had hurt as deeply as our reckoning with the poor quality of the building stock we called our homes, the deceitful practices of contractors who built them, and the corruption of regulators who turned a blind eye. Erdoğan was elected in 2002, three years after that earthquake, and in the context of mass demoralization. Reversing the societal sentiment of being abandoned by the government became a key trope of Erdoğan’s ascendancy.

As everyone was gathering themselves from the mental and physical debris, the government gave big promises to its people. The leaders gave stern speeches about how there would be more rigorous building regulations. These regulations were firmer on paper of course, but they failed in implementation. Twenty-four years later, on February 6, 2023, a magnitude of 7.8 hit Turkey and Syria. Once again at the break of dawn, buildings were flattened, roads were ripped apart and thousands of people were trapped underneath the concrete. In freezing winter conditions, survivors were left on the street without any help, food, or water. Even the people who were pulled from the rubbles in the early hours of that night were faced with the risk of freezing to death. Yes, this was a natural disaster in vast proportions, but what made it this deadly and the suffering so deep was not nature itself, it was the human-built systems of corruption and inequality. The death toll is reaching 48,000 as of today.

There is an interrelationship between a country without democracy and the scale of destruction that occurs after a natural disaster. In a democracy that functions, people in power can be held accountable, and a system exists where checks and balances control spending and the people are informed at each step. Where there is no democracy, there is more suffering.

During the government’s response, Erdoğan admitted to “shortcomings” and blamed the weather, mentioning it was impossible to prepare for a disaster of this level, which is simply incorrect. An earthquake with this high of a magnitude would have caused extreme damage anywhere, but not on such a gruesome scale if the buildings were constructed up to code, and there was proper coordination of rescue efforts. During his visit to one disaster zone, Erdoğan blamed fate and added, “Such things have always happened. It’s part of destiny’s plan.” The implication is that Erdoğan couldn’t have done anything to stop the extent of the human cost. An earthquake is part of destiny, a situation that we might face one day, and a part of nature. This isn’t special to Turkey either, it is a reality that has been and will be part of human civilization. But there is one thing that isn’t destiny: those buildings collapsing and people dying.

In the past two decades, Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party [A.K.P.] have prioritized construction as a motor of economic growth. Initially, during his time in office, bureaucratic and nongovernmental institutions tried to regulate the construction sector, all while keeping the 1999 earthquake in mind. Yet after the constitutional amendments in 2017, Erdoğan established a new presidential regime with almost no checks and balances. He hollowed out bureaucratic institutions, placed loyalists in key positions, and enriched crony contractors. He did not impose necessary construction regulations. Instead, he gave amnesty to the owners of millions of faulty buildings as part of a populist policy that also raised taxation. After the recent earthquake, videos of the president bragging about this “amnesty” are going viral.

There is so much anger and grief that people are fluctuating in between. One minute they are crying uncontrollably, another minute they are burning with outrage, but everyone is consumed by a sense of brokenness. It feels as if our souls have gotten sick, and something collapsed in the collective psyche during the earthquake.

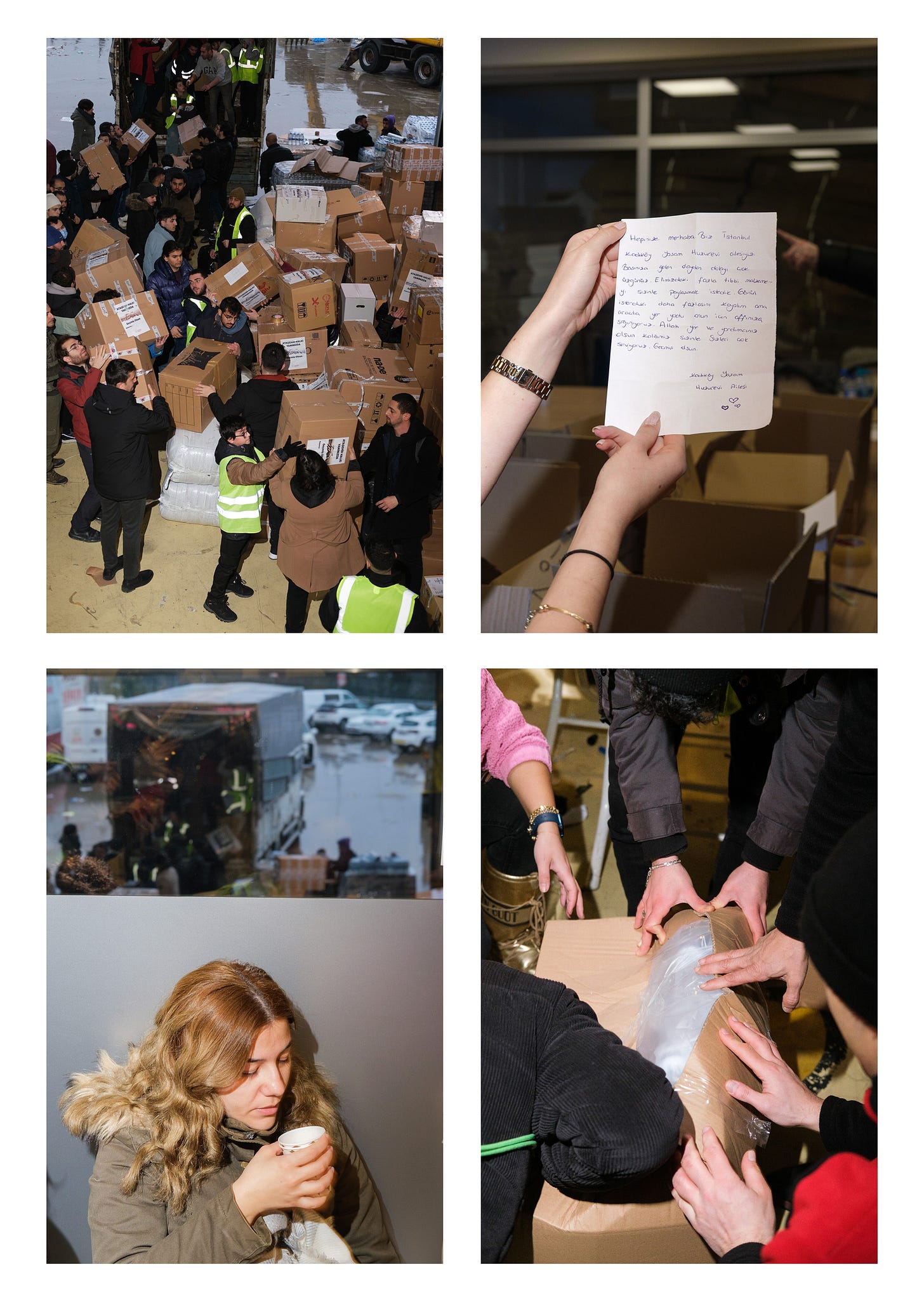

People assumed that a trustworthy government prioritizing the common good would respond more efficiently than uncoordinated, decentralized mass mobilization. But that has not been the case in an environment of mistrust. Volunteers are not merely filling a vacuum. The agility of spontaneous solutions is rarely matched by centralized coordination. Turkish citizens outside the quake zones were much faster and more willing to act than AFAD [Disaster and Emergency Management Authority]—the public agency responsible for disaster management, which is controlled by the presidential office. Thousands of citizens have participated in a gargantuan collective mobilization to assist rescue and humanitarian efforts before any AFAD teams arrived in affected towns.

Many citizens do not trust state officials and witness how civilian efforts surpass state efforts in agility, speed, and most importantly, impartiality. The majority of Turkey doesn’t trust the government and its partisan, politicized institutions. After the 1999 earthquake, multiple organizations for rescue efforts were initiated by civilians, such as AKUT Search and Rescue Association, AHBAP, NGO, and AKOM. Since these were the most trusted organizations, they became a beacon of hope for a myriad of people. AKOM was founded to mitigate the damages caused by natural disasters in Turkish cities. The center is still active to this day, and its team and volunteers get continuous education on disaster prevention to be prepared for when natural disasters occur in Turkey.

Inside AKOM Ataşehir, a district in İstanbul, more than 150 volunteers and members of the government are working 24/7 to get people affected by the earthquake emergency supplies. Within the chaos of it all, everyone works with impeccable momentum. Teams of volunteers make sure each item sent by the civilians is categorized into proper sections before they are sent off to disaster zones. In the first four days, AKOM Ataşehir alone saved 16 people from the rubble. They also have two out of the 30 rescue dogs that are used in the country, named Rex and Tokyo. AKOM’s procedure for gathering and sending items is effective and organized. The crisis center makes sure to keep a list of the needed items and send out calls to the public. Through first-hand contact with the people of İstanbul, they direct the turnover of the supplies and send out the list to the people in charge of the loading area. Each truck is designated for specific items and strict lists are kept to make sure nothing is left behind, and all needed items are sent to each city in their designated truck.

One of the coordinators of AKOM Ataşehir mentioned the sense of solidarity people are experiencing and added how people only focus on working together and being there for our people. This relates to the current climate, too. After years of suffering through polarization by Erdoğan and A.K.P., a sense of comfort is felt by each individual that this unity hasn’t been lost completely. Between two equally devastating earthquakes in 1999 and 2023, Turkey seems to have moved from feeling like a society abandoned by a fragmented state to one that is still feeling uncared for because it is cornered by the jealous whims of a possessive autocrat. Autocratic acts of possessiveness and the polarizing distrust these acts fuel might be the greatest barriers preventing citizens from benefiting from their own collective altruism, which the people of Turkey have generously activated in the hours since the earthquake. There have been miracles happening still today, such as the 21-day-old baby rescued after six days underneath the rubble, the man who hugged each one of his rescuers after being pulled out, and people that are still being saved to this day. There have been incredible moments of resilience and unity since.

The 1999 earthquake in Turkey exposed the shortcomings of the government's emergency response and highlighted the inadequacy of the building regulations. The current government's prioritization of construction as an economic growth factor has neglected the implementation of essential regulations, creating a dangerous situation for citizens. The recent earthquake has once again highlighted the sense of unity and solidarity and is a testament to the resilience and compassion of the Turkish people, who have shown time and time again that they can come together in times of crisis to support one another and help rebuild their communities. This sense of unity is not limited to Turkey, as the international community has also stepped up to provide support to the victims and their families. The fact that people from all over the world are coming together to help those affected by the earthquake is a testament to the power of humanity to unite in the face of tragedy.

The devastating effects of earthquakes are unavoidable, but human-built systems can mitigate the damage, and a functioning democracy is essential in ensuring accountability and public safety. The citizens of Turkey deserve better, and it is time for a government that prioritizes the safety and well-being of its people.

Photographs by Ludvig Perés.